Linux kernel heap quarantine versus use-after-free exploits

It's 2020. Quarantines are everywhere – and here I'm writing about one, too. But this quarantine is of a different kind. In this article I'll describe the Linux Kernel Heap Quarantine that I developed for mitigating kernel use-after-free exploitation.

I will also summarize the discussion about the prototype of this security feature on the Linux Kernel Mailing List (LKML).

Use-after-free in the Linux kernel

Use-after-free (UAF) vulnerabilities in the Linux kernel are very popular for exploitation. There are many exploit examples, some of them include:

UAF exploits usually involve heap spraying.

Generally speaking, this technique aims to put attacker-controlled bytes at a defined memory

location on the heap. Heap spraying for exploiting UAF in the

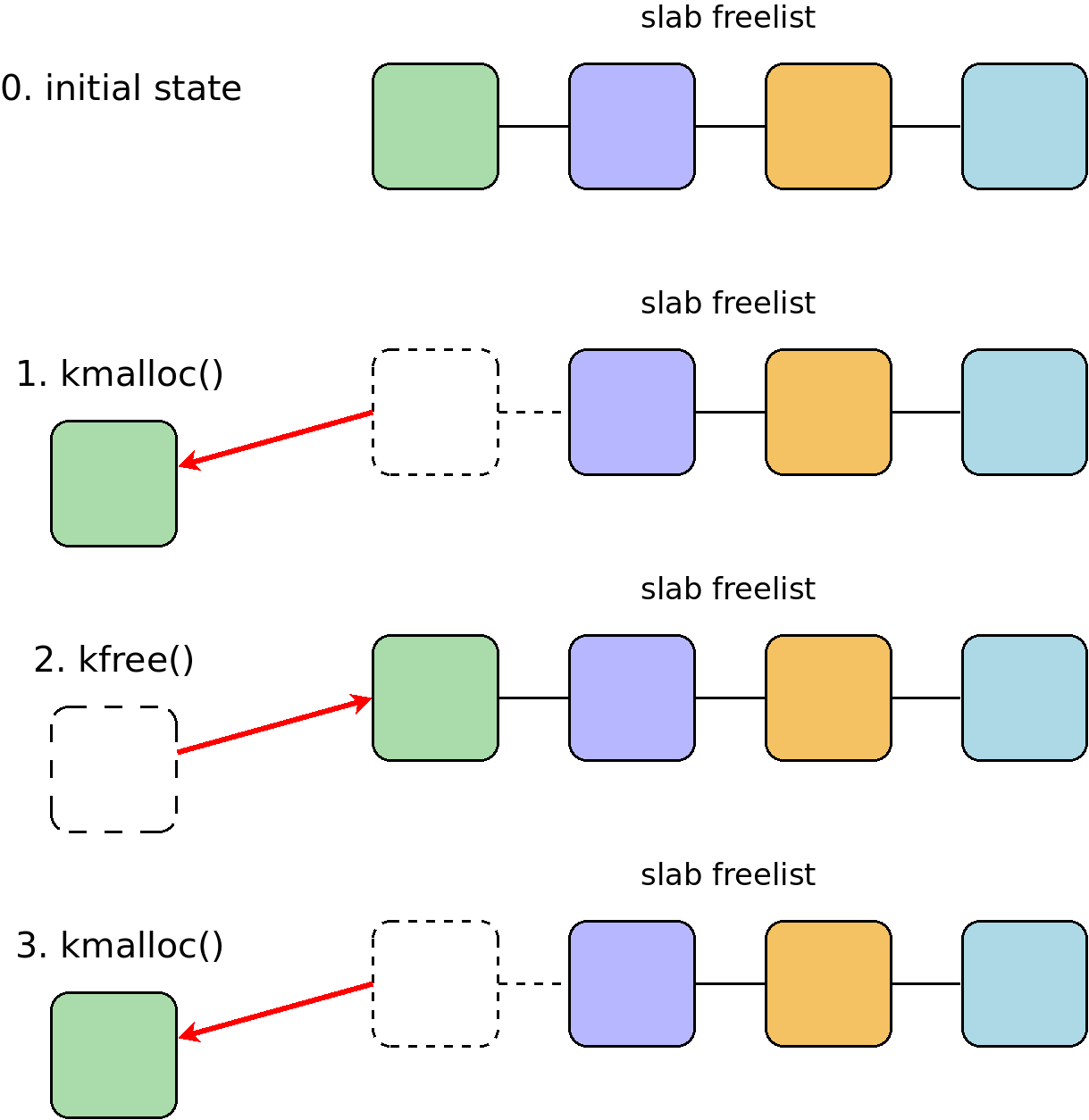

Linux kernel relies on the fact that when kmalloc() is called, the slab

allocator returns the address of memory that was recently freed:

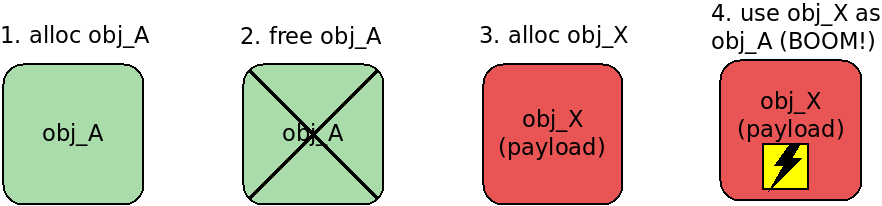

So allocating a kernel object with the same size and attacker-controlled contents allows overwriting the vulnerable freed object:

Note: Heap spraying for out-of-bounds exploitation is a separate technique.

An idea

In July 2020, I got an idea of how to break this heap spraying technique for UAF

exploitation. In August I found some time to try it out. I extracted the slab

freelist quarantine from KASAN functionality and called it SLAB_QUARANTINE.

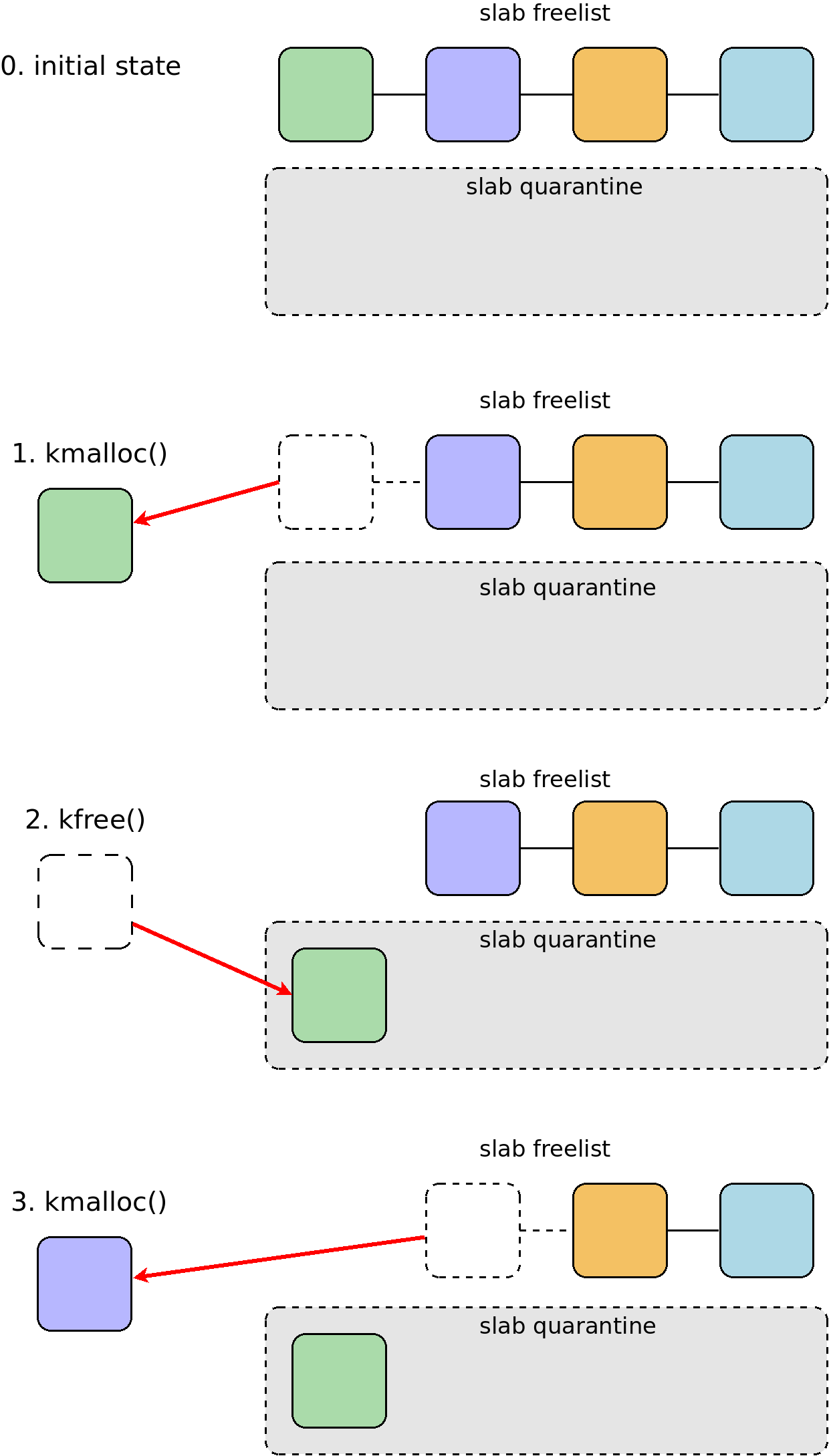

If this feature is enabled, freed allocations are stored in the quarantine

queue, where they wait to be actually freed. So there should be no way for them

to be instantly reallocated and overwritten by UAF exploits.

In other words, with SLAB_QUARANTINE, the kernel allocator behaves like so:

On August 13, I sent the first early PoC to LKML and started deeper research of its security properties.

Slab quarantine security properties

For researching the security properties of the kernel heap quarantine, I developed

two lkdtm tests (code is available here).

The first test is called lkdtm_HEAP_SPRAY. It allocates and frees an object

from a separate kmem_cache and then allocates 400,000 similar objects.

In other words, this test attempts an original heap spraying technique for UAF

exploitation:

#define SPRAY_LENGTH 400000

...

addr = kmem_cache_alloc(spray_cache, GFP_KERNEL);

...

kmem_cache_free(spray_cache, addr);

pr_info("Allocated and freed spray_cache object %p of size %d\n",

addr, SPRAY_ITEM_SIZE);

...

pr_info("Original heap spraying: allocate %d objects of size %d...\n",

SPRAY_LENGTH, SPRAY_ITEM_SIZE);

for (i = 0; i < SPRAY_LENGTH; i++) {

spray_addrs[i] = kmem_cache_alloc(spray_cache, GFP_KERNEL);

...

if (spray_addrs[i] == addr) {

pr_info("FAIL: attempt %lu: freed object is reallocated\n", i);

break;

}

}

if (i == SPRAY_LENGTH)

pr_info("OK: original heap spraying hasn't succeeded\n");

If CONFIG_SLAB_QUARANTINE is disabled, the freed object is instantly

reallocated and overwritten:

# echo HEAP_SPRAY > /sys/kernel/debug/provoke-crash/DIRECT

lkdtm: Performing direct entry HEAP_SPRAY

lkdtm: Allocated and freed spray_cache object 000000002b5b3ad4 of size 333

lkdtm: Original heap spraying: allocate 400000 objects of size 333...

lkdtm: FAIL: attempt 0: freed object is reallocated

If CONFIG_SLAB_QUARANTINE is enabled, 400,000 new allocations don't overwrite

the freed object:

# echo HEAP_SPRAY > /sys/kernel/debug/provoke-crash/DIRECT

lkdtm: Performing direct entry HEAP_SPRAY

lkdtm: Allocated and freed spray_cache object 000000009909e777 of size 333

lkdtm: Original heap spraying: allocate 400000 objects of size 333...

lkdtm: OK: original heap spraying hasn't succeeded

That happens because pushing an object through the quarantine requires both allocating and freeing memory. Objects are released from the quarantine as new memory is allocated, but only when the quarantine size is over the limit. And the quarantine size grows when more memory is freed up.

That's why I created the second test, called lkdtm_PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE.

It allocates and frees an object from a separate kmem_cache and then performs

kmem_cache_alloc()+kmem_cache_free() for that cache 400,000 times.

addr = kmem_cache_alloc(spray_cache, GFP_KERNEL);

...

kmem_cache_free(spray_cache, addr);

pr_info("Allocated and freed spray_cache object %p of size %d\n",

addr, SPRAY_ITEM_SIZE);

pr_info("Push through quarantine: allocate and free %d objects of size %d...\n",

SPRAY_LENGTH, SPRAY_ITEM_SIZE);

for (i = 0; i < SPRAY_LENGTH; i++) {

push_addr = kmem_cache_alloc(spray_cache, GFP_KERNEL);

...

kmem_cache_free(spray_cache, push_addr);

if (push_addr == addr) {

pr_info("Target object is reallocated at attempt %lu\n", i);

break;

}

}

if (i == SPRAY_LENGTH) {

pr_info("Target object is NOT reallocated in %d attempts\n",

SPRAY_LENGTH);

}

This test effectively pushes the object through the heap quarantine and reallocates it after it returns back to the allocator freelist:

# echo PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE > /sys/kernel/debug/provoke-crash/

lkdtm: Performing direct entry PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE

lkdtm: Allocated and freed spray_cache object 000000008fdb15c3 of size 333

lkdtm: Push through quarantine: allocate and free 400000 objects of size 333...

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 182994

# echo PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE > /sys/kernel/debug/provoke-crash/

lkdtm: Performing direct entry PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE

lkdtm: Allocated and freed spray_cache object 000000004e223cbe of size 333

lkdtm: Push through quarantine: allocate and free 400000 objects of size 333...

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 186830

# echo PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE > /sys/kernel/debug/provoke-crash/

lkdtm: Performing direct entry PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE

lkdtm: Allocated and freed spray_cache object 000000007663a058 of size 333

lkdtm: Push through quarantine: allocate and free 400000 objects of size 333...

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 182010

As you can see, the number of the allocations needed for overwriting the vulnerable object is almost the same. That would be good for stable UAF exploitation and should not be allowed. That's why I developed quarantine randomization. This randomization required very small hackish changes to the heap quarantine mechanism.

The heap quarantine stores objects in batches. On startup, all quarantine batches are filled by objects. When the quarantine shrinks, I randomly choose and free half of objects from a randomly chosen batch. The randomized quarantine then releases the freed object at an unpredictable moment:

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 107884

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 265641

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 100030

lkdtm: Target object is NOT reallocated in 400000 attempts

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 204731

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 359333

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 289349

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 119893

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 225202

lkdtm: Target object is reallocated at attempt 87343

However, this randomization alone would not stop the attacker: the quarantine stores the attacker's data (the payload) in the sprayed objects! This means the reallocated and overwritten vulnerable object contains the payload until the next reallocation (very bad!).

This makes it important to erase heap objects before placing them in the heap quarantine.

Moreover, filling them with zeros gives a chance to detect UAF

accesses to non-zero data for as long as an object stays in the quarantine (nice!).

That functionality already exists in the kernel, it's called init_on_free.

I integrated it with CONFIG_SLAB_QUARANTINE as well.

During that work I found a bug: in CONFIG_SLAB, init_on_free happens too

late. Heap objects go to the KASAN quarantine while still "dirty." I provided the fix

in a separate patch.

For a deeper understanding of the heap quarantine's inner workings, I provided an additional patch, which contains verbose debugging (not for merge). It's very helpful, see the output example:

quarantine: PUT 508992 to tail batch 123, whole sz 65118872, batch sz 508854

quarantine: whole sz exceed max by 494552, REDUCE head batch 0 by 415392, leave 396304

quarantine: data level in batches:

0 - 77%

1 - 108%

2 - 83%

3 - 21%

...

125 - 75%

126 - 12%

127 - 108%

quarantine: whole sz exceed max by 79160, REDUCE head batch 12 by 14160, leave 17608

quarantine: whole sz exceed max by 65000, REDUCE head batch 75 by 218328, leave 195232

quarantine: PUT 508992 to tail batch 124, whole sz 64979984, batch sz 508854

...

The heap quarantine PUT operation you see in this output happens during kernel memory freeing.

The heap quarantine REDUCE operation happens during kernel memory allocation, if the quarantine

size limit is exceeded. The kernel objects released from the heap quarantine return to the allocator

freelist – they are actually freed.

In this output, you can also see that on REDUCE, the quarantine releases some part of

a randomly chosen object batch (see the randomization patch for more details).

What about performance?

I made brief performance tests of the quarantine PoC on real hardware and in virtual machines:

-

Network throughput test using

iperf

server:iperf -s -f K

client:iperf -c 127.0.0.1 -t 60 -f K -

Scheduler stress test

hackbench -s 4000 -l 500 -g 15 -f 25 -P -

Building the defconfig kernel

time make -j2

I compared vanilla Linux kernel in three modes:

init_on_free=offinit_on_free=on(upstreamed feature)CONFIG_SLAB_QUARANTINE=y(which enablesinit_on_free)

Network throughput test with iperf showed that:

init_on_free=ongives 28.0 percent less throughput compared toinit_on_free=off.CONFIG_SLAB_QUARANTINEgives 2.0 percent less throughput compared toinit_on_free=on.

Scheduler stress test:

- With

init_on_free=on,hackbenchworked 5.3 percent slower versusinit_on_free=off. - With

CONFIG_SLAB_QUARANTINE,hackbenchworked 91.7 percent slower versusinit_on_free=on. Running this test in a QEMU/KVM virtual machine gave a 44.0 percent performance penalty, which is quite different from the results on real hardware (Intel Core i7-6500U CPU).

Building the defconfig kernel:

- With

init_on_free=on, the kernel build went 1.7 percent more slowly compared toinit_on_free=off. - With

CONFIG_SLAB_QUARANTINE, the kernel build was 1.1 percent slower compared toinit_on_free=on.

As you can see, the results of these tests are quite diverse and depend on the type of workload.

Sidenote: There was NO performance optimization for this version of the heap quarantine prototype. My main effort was put into researching its security properties. I decided that performance optimization should be done further on down the road, assuming that my work is worth pursuing.

Сounter-attack

My patch series got feedback on the LKML. I'm grateful to Kees Cook, Andrey Konovalov, Alexander Potapenko, Matthew Wilcox, Daniel Micay, Christopher Lameter, Pavel Machek, and Eric W. Biederman for their analysis.

And the main kudos go to Jann Horn, who reviewed the security properties of my slab quarantine mitigation and created a counter-attack that re-enabled UAF exploitation in the Linux kernel.

Amazingly, that discussion with Jann happened during Kees's Twitch stream in which he was testing my patch series (by the way, I recommend watching the recording).

Quoting the mailing list:

On 06.10.2020 21:37, Jann Horn wrote:

> On Tue, Oct 6, 2020 at 7:56 PM Alexander Popov wrote:

>> So I think the control over the time of the use-after-free access doesn't help

>> attackers, if they don't have an "infinite spray" -- unlimited ability to store

>> controlled data in the kernelspace objects of the needed size without freeing them.

[...]

>> Would you agree?

>

> But you have a single quarantine (per CPU) for all objects, right? So

> for a UAF on slab A, the attacker can just spam allocations and

> deallocations on slab B to almost deterministically flush everything

> in slab A back to the SLUB freelists?

Aaaahh! Nice shot Jann, I see.

Another slab cache can be used to flush the randomized quarantine, so eventually

the vulnerable object returns into the allocator freelist in its cache, and

original heap spraying can be used again.

For now I think the idea of a global quarantine for all slab objects is dead.

I shared that in Kees's Twitch stream chat right away, and Kees adapted my

PUSH_THROUGH_QUARANTINE test to implement this attack. It worked. Bang!

Further ideas

Jann proposed another idea for mitigating UAF exploitation in the Linux kernel. Kees, Daniel Micay, Christopher Lameter, and Matthew Wilcox commented on it. I'll give a few quotes from consecutive messages here to describe the idea. However, I recommend reading the whole discussion.

Jann:

Things like preventing the reallocation of virtual kernel addresses

with different types, such that an attacker can only replace a UAF object

with another object of the same type.

...

And, to make it more effective, something like a compiler plugin to

isolate kmalloc(sizeof(<type>)) allocations by type beyond just size

classes.

Kees:

The large trouble are the kmalloc caches, which don't have types

associated with them. Having implicit kmem caches based on the type

being allocated there would need some pretty extensive plumbing, I

think?

Jann:

You'd need to teach the compiler frontend to grab type names from

sizeof() and stuff that type information somewhere, e.g. by generating

an extra function argument referring to the type, or something like that.

Daniel:

It will reuse the memory for other things when the whole slab is freed

though. Not really realistic to change that without it being backed by

virtual memory along with higher-level management of regions to avoid

intense fragmentation and metadata waste. It would depend a lot on

having much finer-grained slab caches.

Christopher:

Actually typifying those accesses may get rid of a lot of kmalloc

allocations and could help to ease the management and control of objects.

It may be a big task though given the ubiquity of kmalloc and the need to

create a massive amount of new slab caches. This is going to reduce the

cache hit rate significantly.

Conclusion

Prototyping a Linux kernel heap quarantine and testing it against use-after-free exploitation techniques was a quick and interesting research project. It didn't turn into a final solution suitable for the mainline, but it did give us useful results and ideas. I've written this article as a way to summarize these efforts for future reference.

And for now, let me finish with a tiny poem that I composed several days ago before going to sleep:

Quarantine patch version three

Won't appear. No need.

Let's exploit use-after-free

Like we always did ;)

-- a13xp0p0v